The Data Logging Cycle

Overview

Teaching: 20 min

Exercises: 0 minQuestions

Why is the ModularSensors library necessary, and how does it make it easier to program a data logger?

Objectives

Learn the basic steps of a data logging cycle.

Episode 8: The Data Logging Cycle

DIYers generally find rapid success at reading data from simple sensors to an Arduino board. However, it is much more challenging to program an Arduino to perform all required functions of a solar-powered station that collects data from several research-grade environmental sensors, saves to an SD card, transmits to a public server with web services, and puts the sensors to sleep to conserve energy between logging intervals. The EnviroDIY ModularSensors library was designed coordinate these tasks.

Let’s dig in study the various steps of a data logging cycle, along with additional things a data logger needs to do.

Timing, Sleep and Wake

A datalogger needs to carefully keep track of time for a wide variety of purposes:

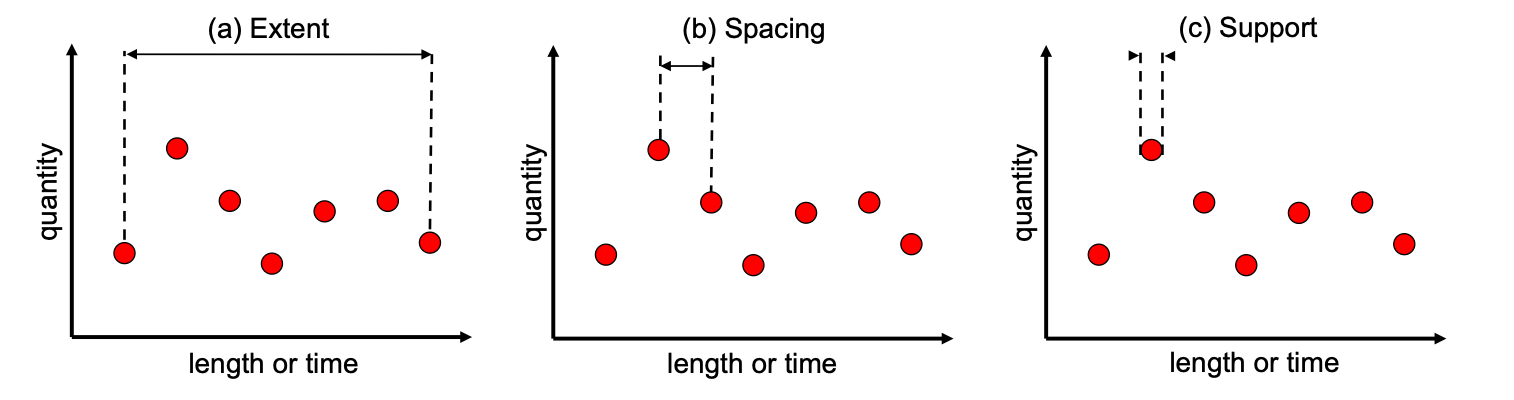

- Logging interval(s), or time spacing, between recording measurements.

- Keeping track of logging/recording intervals is complicated by the need to align logging to time stamps on a real time clock, which is a separate device from the micro-controller chip, and the imperative to put the logger into a deep, power-saving sleep mode between recording measurements.

- Sometimes it is useful for a single datalogger to log different measurements at different intervals.

- Sensor warm up time, before it can start sending data or receiving commands after it is powered up.

- Sensor stabilization time, before it can start providing reliably stable or precise data after it is powered up.

- Sensor measurement time, or scan interval, is how long the sensor takes to make a single measurement before it can make another.

- Sensor number of readings, which is how many individual measurements get made, one after another, to then be averaged for the recorded result for that logging interval.

- Most sensors benefit from averaging multiple readings, to reduce signal noise. Many commercial sensors with built-in dataloggers, do this by default.

- Sensor averaging time, or time support, is the product of measurement time and number of readings.

- Sometimes it is useful to average over a long-enough time to average-out the effects of higher-frequency environmental variability than what you are studying, such as the pulses of turbidity that go up and down every 3-10 seconds with passing eddies and vortices.

Figure from Jeff Horsburgh’s lecture 6 in his 2016 HydroInformatics (USU CEE-6110) class.

Figure from Jeff Horsburgh’s lecture 6 in his 2016 HydroInformatics (USU CEE-6110) class.

Take home on Timing

- Selecting a Logging Interval is a balance between choosing a small-enough interval to capture the environmental dynamics of interest versus selecting a longer interval that minimizes your radio communication costs and preserves the solar charging capacity of your station.

- Typical logging intervals range from 5 to 30 minutes. A 15 minute interval is most common.

- Specifying sensor warmup, stabilization, and measurement times typically requires studying the sensor manufacturer’s specification sheet, but sometimes requires experimenting with the sensor.

- Deciding on an optimal number of readings and/or averaging time for a sensor typically requires experimenting with the sensor.

Collecting Data from Various Sensors

A key requirement of any datalogger is to mediate all of the communications with different kinds of sensors. Data loggers are designed to potentially interface with hundreds of different sensors from dozens of manufacturers. Fortunately, there are only about a dozen communication protocols used by environmental sensors, such as:

- Analog to Digital Conversion (ADC)

- TTL Serial

- I2C

- RS232 Serial

- OneWire

- AT

- NMEA

- SDI12

- Modbus

Some of these are native to the Arduino microcontroller hardware (e.g. ADC; TTL Serial) and standard libraries (e.g. I2C), while others are enabled by widely-used community libraries (e.g. RS232 Serial, OneWire, AT). Several specialized communication protocols also exist for environmental and industrial applications (e.g. NMEA, SDI12, Modbus).

Some of these communication protocols are “smart”, in that the sensor might have an ID, or address, so that many sensors of a similar type can be connected to the same set of wires. These smart sensors often expect to receive a command before making a measurement and returning data, many of these can also be asked to return additional information, such as a serial number or calibration coefficients. Other sensors are passive, and just start return values shortly after they receive power.

Another key requirement of any data logger is to provide the appropriate power to each sensor. Most sensors have specified:

- Voltage range (measured in volts of direct current (VDC))

- if supplied voltage is too low, the sensor will not respond.

- if supplied voltage is too high, the sensor may become damaged.

- a sensor’s voltage range is typically specified in its spec sheet.

- Current draw (measured in amps (A) or milliamps (mA)).

- the power supplied from a logger to a sensor always has a maximum upper limit to the current it can provide to all the sensors on that power line (which is often shared internally within the logger). Exceeding this limit will cause the sensor to “brown out”.

- current draw is also useful for calculating solar charging requirements. NOTE that current times voltage equals power (measured in Watts), or V * A = W.

- a sensor’s common or maximum current draw is sometimes specified in its spec sheet, but real world current usage most often can only be quantified as directly measured by the user.

Writing Data to an SD Card

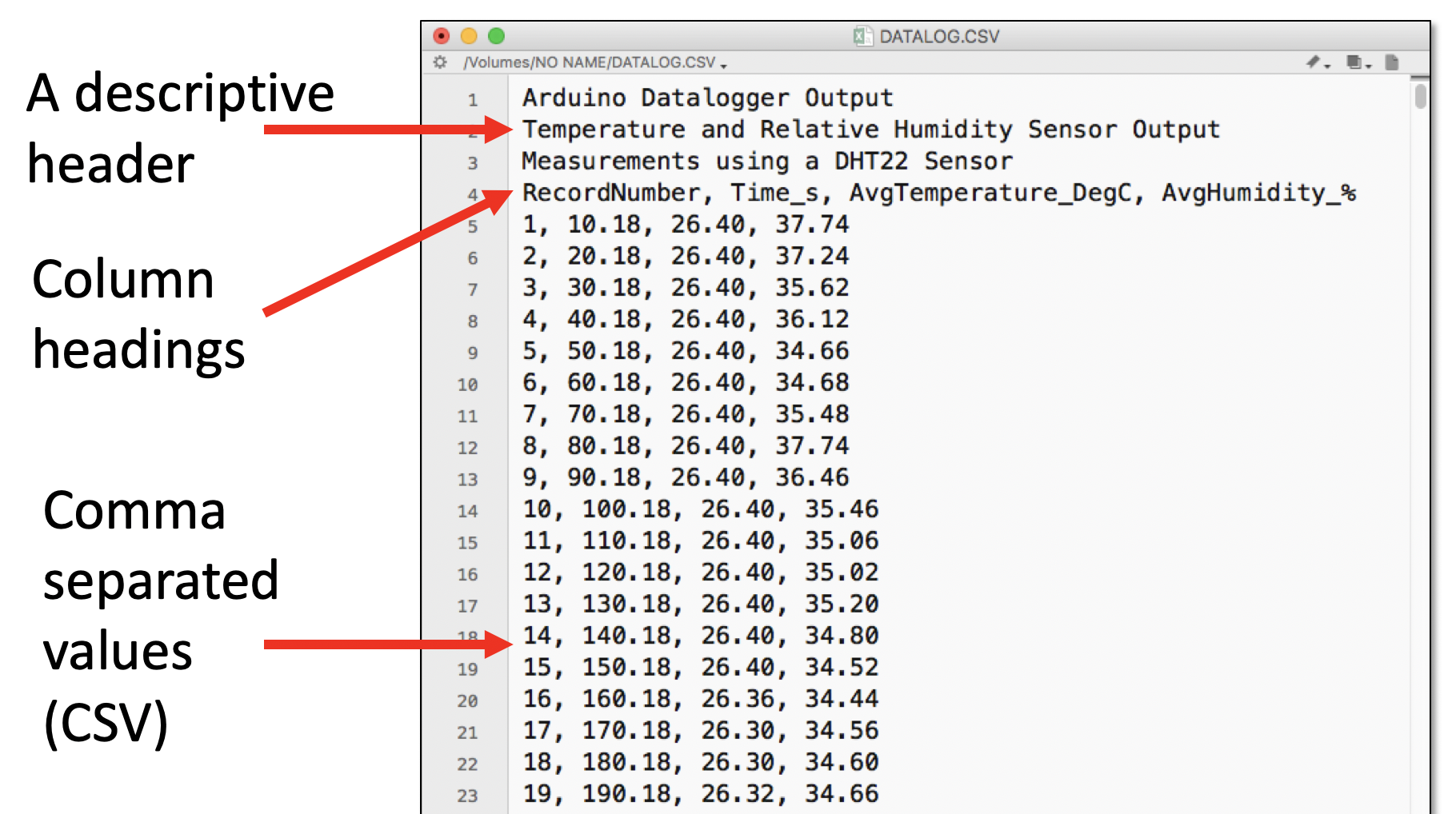

Once a datalogger had retreived data values from each of the connected sensors, it needs to write those values from short-term memory (i.e. which is erased when the microcontroller is turned off) to a form of long-term data storage (i.e. which can persist for decades even with no power). To do this, the data values need to be organized into a comma-separated string of numbers and characters, along with the date-time at which the measurements were made. For the user to make sense of the data later, the datalogger also needs to record “headers”, which are one or more special rows that contain information about the entire file and also what is found in each column, such as the sensor name, variable name and units

Figure from Jeff Horsburgh’s lecture 7 in his 2016 HydroInformatics (USU CEE-6110) class.

Figure from Jeff Horsburgh’s lecture 7 in his 2016 HydroInformatics (USU CEE-6110) class.

Transmitting Data via Radio

A wireless datalogger needs to:

- control the radio, so that it can connect to an internet hub and knows when the requested communication has completed.

- connect to a server that is set up to receive the data.

- format the data in the proper format that the data server expects and knows how to parse.

Debugging

Few users can setup a programable datalogger without encountering errors. The key to fixing these errors is a datalogger program that provides meaningful output describing where those errors might have occurred. Debugging information might answer such questions as:

- Did the sensor respond at all to a request for data?

- Was the response from the sensor a valid data value?

- Did the logger successfully write to the storage card/chip?

Key Points

All dataloggers manage a common sequence of steps, each of which requires coordination of many individual and often complex tasks.